Forks: Not Just for Eating Cows

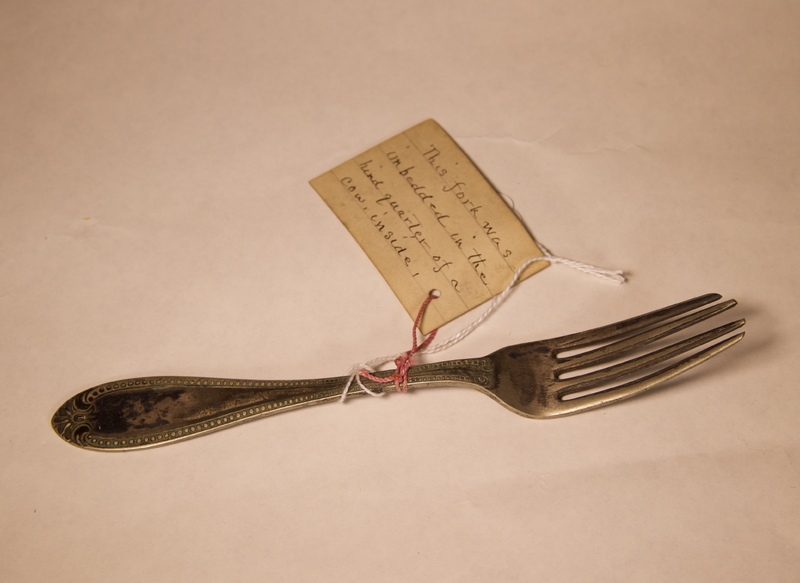

According to museum staff, this fork was found by a local farmer embedded in the hind quarter of one of his cows. After recovering it, the farmer brought the fork to Sheldon for preservation in the museum. It is accompanied by a tag handwritten by Sheldon which provides a vague account of the fork’s origin. The tag reads: “This fork was imbedded [sic] in the hind quarter of a cow, inside”. Apart from obvious signs of age, the fork appears unremarkable. Certainly nothing in its appearance explains why or how the utensil was inserted into a living animal. Many details are also left unclear, including the presence of an entry wound in the cow, how far in the animal the fork was found, and how the farmer became aware of the cow’s injury. Sheldon’s use of the term “imbedded” [sic] is vague, and only implies the fork is in the cow to some degree, but his subsequent use of the term “inside” suggests the fork was completely inserted in the animal, which is not what would immediately be assumed. The outlandish nature of this artifact’s background also brings into question the authenticity of the story as a whole, as it is not impossible the farmer invented the tale in order to have recognition of some sort in Sheldon’s museum. However, this possibility seems unlikely considering the specificity of the farmer’s claims as well as the lack of documentation of the farmer’s name today.

Understandably, many may question the historical value of such an artifact. The unremarkable appearance of the fork itself, as well as anecdotal quality of the accompanying story, might cause modern day observers to doubt the object’s ability to provide any useful insight into the past. In fact, some go so far as to label such items in Sheldon’s collection as “junk” (“Discover”). Merriam-Webster defines junk as "something of little meaning, worth, or significance", but further examination of the fork demonstrates the object does not fit within this definition.

The unexceptional appearance of the physical fork should not cause viewers to classify the utensil as historically useless, as the connected story is what gives the utensil meaning. In Sheldon’s era, many historical artifacts were similar to the fork in the way they were visually unstimulating, but gained meaning through their context. Objects in the collection of the United States National Museum, the predecessor to the National Museum of American History in Sheldon's time, included fragments of Roman mosaics and a piece of wood from a railroad tie in Promontory, Utah. Both items might seem plain upon inspection, but understanding the story behind each artifact could illuminate their significance (Bird 2013, 11). Comparing these types of artifacts, the standard of Sheldon’s time period, with objects in his museum, such as the fork, exhibits Sheldon’s collection as one not comprised of random junk items, but rather of objects with hidden significance. Accepting this idea, the question remains: exactly what significance could oddities such as the fork be hiding for modern observers?

In order to understand the fork’s current relevance, it is important to first comprehend Henry Sheldon’s original intent of his collection so the artifact may be analyzed with this context in mind. Early in the museum's existence, Sheldon collected historical Middlebury newspapers to preserve local history for future generations (“Henry Sheldon Museum”). Additionally, Sheldon worked to collect strange objects from residents of the region, demonstrated by the advertisements he put in a Middlebury newspaper in which he requested “...any object worthy of preservation...” (Middlebury Register 1888). Realizing Sheldon’s desire to maintain local Vermont history, viewers can interpret the fork as another pathway to an element of Middlebury’s past. The fact a farmer found the utensil in his animal and found the story interesting enough to bring it to Sheldon for preservation must illustrate some aspect of Middlebury’s culture in this time period. This story can be understood as an example of the Middlebury peoples’ inclination to share oddities and strange anecdotes with each other, or simply an amicable small town culture in which residents take interest in what their neighbors have to say. Regardless, the fork and its origin story have historical value in describing nineteenth century Middlebury.

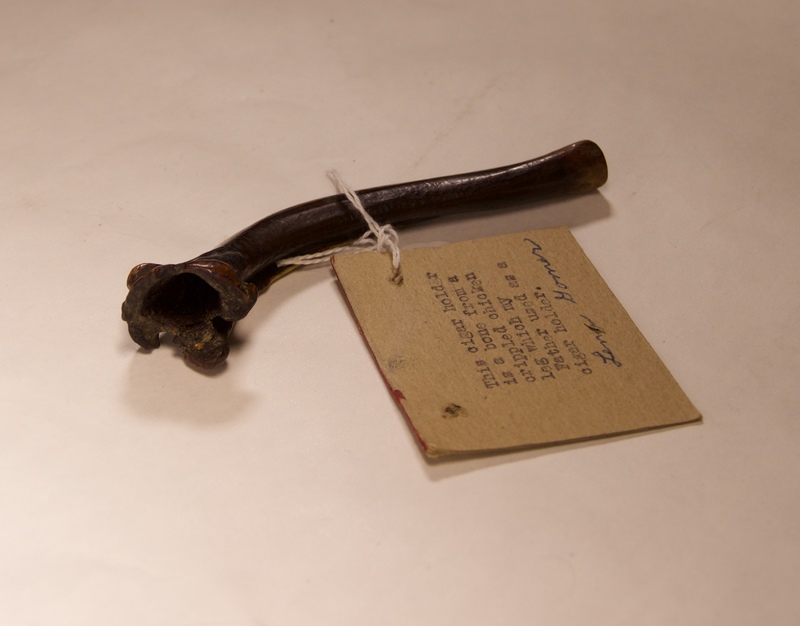

Some of the other objects in Sheldon’s collection appear similarly insignificant, yet also have accompanying circumstances which provide insight into Vermont during the collector’s life. For example, the museum also contains a crippled chicken bone used by Sheldon’s father as a cigar stand. The bone itself holds no special meaning aside from its crippled shape, but Sheldon’s explanation of his father’s use for the bone, as well as his decision to catalogue it in his collection, give modern day viewers a similar snapshot of late 1800s’ Vermont as the fork does. The bone could be interpreted as an interest in the irregular due to the crippled structure of the bone, or even the close-knit nature of the Middlebury community as Sheldon found this familial anecdote worthy of preservation for other residents’ knowledge.

As a whole, the items in Sheldon’s museum fit both the context of his goal to preserve local Middlebury history, as well as the concurrent national trend of keepsakes. Both keepsakes and many objects in Sheldon’s collection seem unimportant based on appearance alone; however, these objects can actually provide useful insight into the past when understood in their context of their background stories. Sheldon's objects differ from the national trend only in the way they preserve a snapshot of the conversations and anecdotes from local Vermonters of the period as opposed to a traditional chronological depiction of history. In this way, Sheldon’s oddities provide a window to a unique aspect of late 1800’s rural Vermont history.