Browse Exhibits (6 total)

Beauty Ideals in Ladies Home Journal

Established in 1883, the Ladies Home Journal remained a popular and successful women's magazine throughout the 20th century.[1] Certainly, the magazine was popular in the decade following World War II, when its combination of fashion, advice literature, social commentary, and romance fiction made it appealing to white, middle-class women. The postwar trend toward earlier marriage and higher fertility can be seen in the magazine's emphasis on domesticity and parenting. But the Journal also offered beauty and fashion tips to the single woman eager to attract a man, and to the housewife eager to remain attractive to her husband. As the items in this collection reveal, beauty was idealized in many ways in the pages of Ladies Home Journal in 1954 - in advice columns, in features on apparel and home fashions, in advertisements for cosmetics, personal hygiene products, clothing, and other products, and in romance stories such as Marnie Ellingson's "The Real You," which is the centerpiece of this exhibit.

----------

1. “Ladies’ Home Journal | American Magazine | Britannica.com.” Accessed October 26, 2016. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ladies-Home-Journal.

Sports Illustrated "The Black Athlete"

Sports Illustrated from July 1, 1968 included feature content about Black athletes, called "The Black Athlete: A Shameful Story." The July 1 issue was the first installment of a five-part series by Jack Olsen. Part 1 is titled "The Cruel Deception" and investigates the notion that sports was the most progressive national arena for positive race relations and opportunity for black youth in mid-twentieth century. Olsen uncovers the many fallacies of this concept by exploring the realm of collegiate athletics. He delves into the social and academic struggles that arise as black youth matriculate into predominantly white universities to play sports, discussing everything from money management, dating, and coursework. The feature draws on the voices of black athletes themselves as they discuss their grievances, their athletic performance, their public activism, and their experience of race in sports. Many of the athletes interviewed were nationally recognized, some professional. Olsen's other interviews ran the gamut from sociologists, to black community leaders, to white athletic directors and coaches. Sports Illustrated deemed this long form essay one of its most important features, and an uncharacteristic dive into the tense racial cauldron of the United States. However, the piece was notably geared only toward white readers. Olsen's language and positioning throughout the piece are telling of audience demographic; he often implies the separation of his readers--and himself--from black communities and the issues they face, in sports and otherwise. Olsen also often identifies as white and acknowledges white cultural ideology, even as he challenges it. The ads embedded in the pages of the story are even more striking. The ads feature only white people, and these figures are usually engaging in traditionally 'white' cultural practices like deep sea fishing and skiing. The feature archived in this collection reveal the ways in which Sports Illustrated used athletics as a context in which to discuss racial tension and oppression with a white readership.

Alcohol in Cosmopolitan Magazine

In the 1950s, Americans used alcohol heavily in their leisure time. Widespread recreational drinking was considered a normal and safe activity for post-World War II Americans (1). Alcohol advertisements from the era show that alcohol was marketed as a signifier of status and sophistication. Alcohol marketing sold not only a beverage or a type of glassware, but the idea of a middle to upper-class, norm-abiding leisurely lifestyle. "Cocktail hour" was a common social ritual (drinks after work, before dinner) for Americans, and consumption of straightforward, no-nonsense cocktails (like the martini) was considered more classy and respectable (1). Moderate to heavy drinking at home played a big part in "the conformist atmosphere of the corporate bureaucracies and suburban enclaves that mushroomed during the 1950s" (2).

This exhibit explores the way that alcohol is represented in a 1953 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine. It includes advertisements for spirits and liqueurs, an article about wine and a blurb about alcohol abuse. Common themes in these materials include the association of certain alcohol products with cultural refinement, wealth, and prestige in the eyes of others. They also stress the geographical/historical roots of the alcohol products (i.e. France for certain spirits, or Kentucky for certain whiskeys) in an attempt to give the company credibility and the product authenticity. In these texts, alcohol and the way it is served represent opportunities for self-expression and social communication of high-class sensibilities.

1. Rotskoff, Lori. Love on the Rocks : Men, Women, and Alcohol in Post-World War II America, 2002, 195.

2. Rotskoff, Lori. Love on the Rocks : Men, Women, and Alcohol in Post-World War II America, 2002, 198.

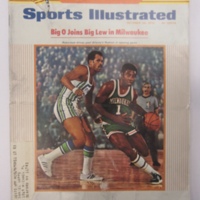

Black Athletes "on the Ropes" with Masculinity

With its first issue published in 1954, Sports Illustrated has gone through decades of transformation. When it first began, its creator—Henry Luce— hoped to expand the types of publications distributed by Time Inc. After Andre Daguerre took over as managing editor in 1960, the popularity of SI grew. [1] They covered all sporting events from basketball and tennis, to skiing and football. With their stories and photos, they allowed their readers to get a glimpse into the lives of American athletic heroes. SI issues went beyond just the plays of the game, game statistics and quality of the players. The articles delivered first-hand accounts of what motivated and frightened the athletes. The articles, whether they meant to or not, served to humanize the athletes and helped sports audiences identify with them.

Three specific articles— “A Rueful Dream Come True,” “Still Too Tender to Be a Tiger” and “He Moves Like Silk, Hits Like a Ton”— were all published towards the end of the 1960s into the early 70s and highlight the stories of two boxers: Muhammad Ali and Floyd Patterson. When analyzed together, not only do the articles detail the social and political transformations in the boxing world, they also comment on the boxers’ masculinity and what was required of athletes to be recognized as serious, All-American, professionals. The items in this collection exhibit how different language is employed by the authors when describing the careers of Ali and Patterson. As a result, Ali is framed as true athlete and hero, while Patterson is framed as a weak, emotional person not fit to fight in the ring.

—————

1. "Sports Illustrated". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. Web. 02 Nov. 2016

<https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sports-Illustrated>.

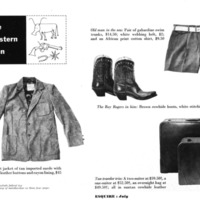

Buying a Lifestyle: Advertising in Esquire during the 1950's

This exhibit details how male-focused advertising brought about the idea of a lifestyle as a brand and how it reenforced the idea that in order to be apart of a certain section of society, one needed the material possessions that signified that they were a man of a certain ilk. These advertisements, drawn from Esquire's fathers day edition in July 1953, are a clear indication of how consumerism began to dictate identity following the ending of World War II. These ads focused on the identification and the compartmentalization of each man into 7 different categories. And while there was some overlap between the seven, it is clear that each lifestyle offers different and unique societal beliefs.

Female Body Agency As Framed By True Confessions

In “How the Other Half Read,” Erin Smith notes the struggle of understanding how working class, marginal readers might react to pulp magazine publications in the mid-twentieth century. “Although wealthy people with access to education and print media leave all sorts of evidence […] that give testimony to what they read and how they read it, the ‘marginal’ readers of pulp magazines were of a social and class position that made it unlikely hey would leave behind this kind of evidence” [1]. But the popularity of pulp magazines speaks to our ability to imply that pulp magazines did accurately represent the marginal readers’ interests—at least enough so that they continued to sell for more than half a century. We can look at materials such as ads within the magazines as “indirect sources, representations of readers’ presumed desires and experiences by ad writers whose primary goal is to sell products, to shape readers into consumers” [2].

This exhibit investigates the October 1956 edition of popular romance pulp True Confessions with a critical lens involving the assumed interests of working class women, the majority audience of such publications [3]. In looking at both structure and content of this specific publication, it becomes clear that heteronormative romance narratives are placed as the central focal point of the publication, with advertisements existing in the periphery and often validating the representation of women in the narratives. Throughout the exhibit, we will look at how the female body is represented in one of the narratives from the October 1956 issue of True Confessions. We will also look at a variety of advertisements, some of which seem to promote female healthy and individuality, and others that clearly promote products for women that are meant for the sole purpose of male appeal. But, based on how the magazine is physically constructed and the narratives that are centra to the publication, I will argue that despite the ads that seem to promote female body agency, the magazine promotes the idea that female body agency is intrinsically linked to alluring the male and that happiness depends on beautification, love, and male attention.

_______

1. Smith, Erin A. “How the Other Half Read: Advertising, Working-Class Readers, and Pulp Magazines.” Book History, vol. 3, 2000, p. 205. www.jstor.org/stable/30227317.

2. ibid, p. 206.

3. ibid, p. 205.