The Under-Lip

The Under-Lip

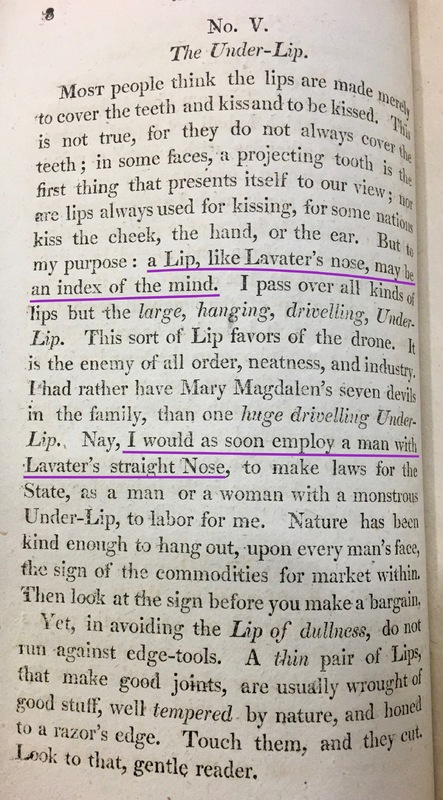

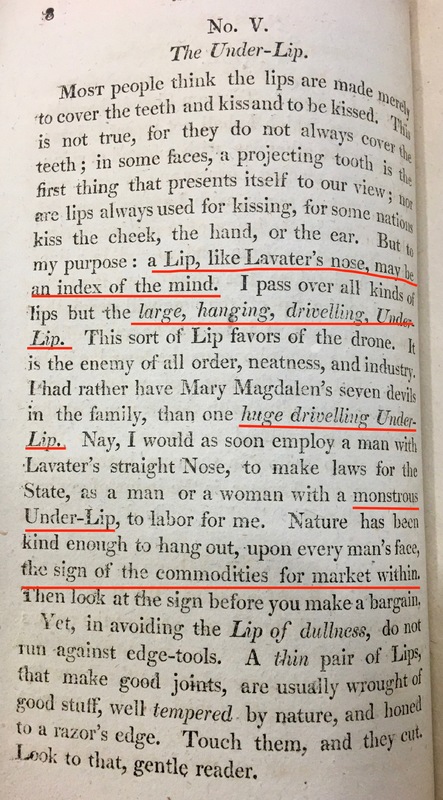

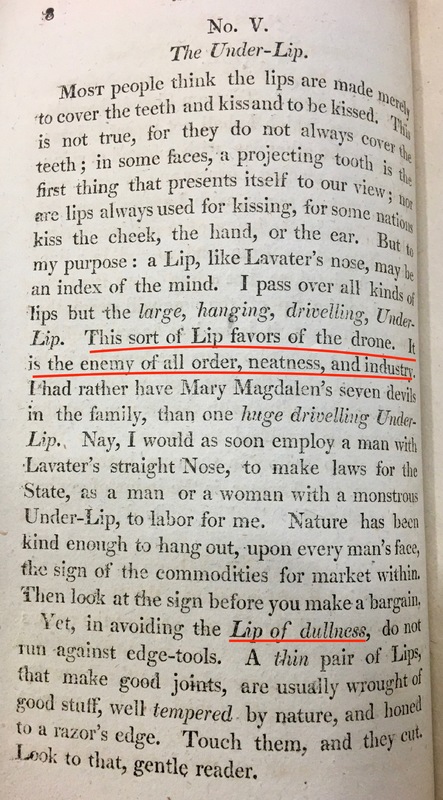

In “The Under-Lip”, Noah Webster uses his assessment of those with under-lips to classify laborers into two groups: capable laborers without under-lips, and incompetent laborers with under-lips. In doing so, Webster rearticulates a class distinction between laborers (who may or may not have under-lips) and his readers, who are assumed to be of a high enough class to hire their own laborers, and not to have under-lips. As he entextualizes his readers’ high-class status, Webster also builds his own ethos as possessing the proper scientific expertise to make such assessments based on lip-type by comparing himself to famous physiologist John Lavater.

Webster's Ethos

Why should anyone believe Webster’s claims about the under-lip? In case his fame was not enough to earn the trust of his readers, Webster attempts to further enhance his ethos in this passage by comparing himself to Johann Caspar Lavater, a famous English physiologist who claimed “he could judge of a man's character by the outline of his features” (Graham 1961). Lavater and his categorization of noses act as another emblem throughout the passage. Webster suggests that “a lip, like Lavater’s nose, may be an index of the mind,” and later compares the under-lip to Lavater’s straight nose. Webster’s comparisons between his analysis of lips and Lavater’s analysis of noses suggests to readers that Webster is well-versed in Lavater’s physiology and therefore qualified to be making such claims about under-lips.

Types of Laborers

Webster’s main purpose in this passage appears to be his evaluation of the under-lip as a marker of an incompetent laborer, thus categorizing laborers as either competent or incompetent. He claims that lips “may be an index of the mind” and are “the sign of the commodities for market within” (Webster 1808: 8). The lips represent how capable a laborer is. Webster goes on to describe the under-lip using words like “large”, “hanging”, “huge”, “monstrous” and “drivelling”, all words which have pre-established negative connotations; someone large, huge, or monstrous is probably not agile; something hanging and drivelling sounds lazy and sluggish. Because Webster as already established a connection between lip and mind, these descriptions of the under-lip are immediately associated with the mind of the possessor of the under-lip, and very few people are apt to hire a clumsy or lazy worker. Thus, Webster creates two classes of potential laborers: those who are should be hired, and those who should not.

In case readers fail to connect these descriptions with the competence of a laborer, Webster intersperses even more explicit explanations of the under-lip’s implications: “This sort of lip favors the drone” he writes; it is the “Lip of dullness”; “It is the enemy of all order, neatness, and industry” (Webster 1808: 8). If readers have trouble picturing what a “large”, “hanging”, “huge”, “monstrous” and “drivelling” laborer might be like, they will have no problem connecting the “drone”, “dullness”, and the antithesis of “order, neatness, and industry” associated with the under-lip to the mind of the laborer who possesses an under-lip. The two types of laborers are becoming even more distinct, those with under-lips are more and more unappealing to employers, and so those without under-lips must by the more desirable laborers.

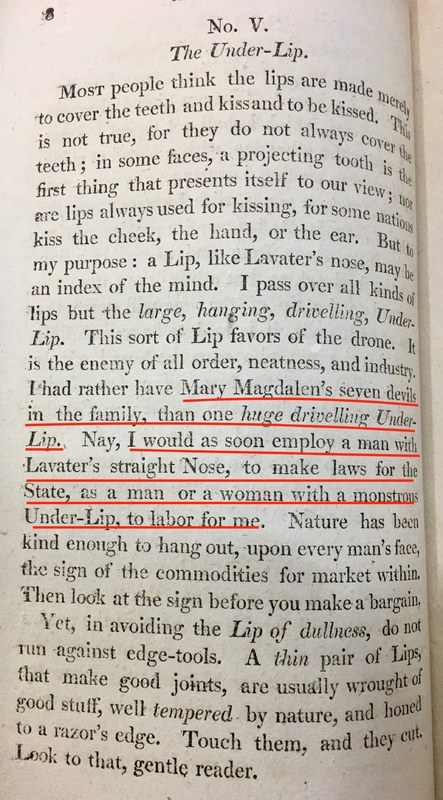

Yet, Webster seems to fear that these descriptions may not be enough to deter readers from hiring those with under-lips, so he takes his descriptions a step further, using emblems – phrases with pre-established meanings that readers at the time would have understood immediately – to emphasize the incompetence of laborers with under-lips. For one, Webster suggests that he “had rather have Mary Magdalen’s seven devils in the family, than one huge drivelling Under-Lip”, and later claims that he “would as soon employ a man with Lavater’s straight nose, to make laws for the state, as a man or woman with a monstrous Under-Lip, to labor for me” (Webster 1808: 8). Webster claims that devils as children, and a politician with Lavater’s straight nose would both be better than an employee with an under-lip. Again, in the most basic terms, the laborer with the under-lip is bad, and so the laborer without the under-lip must be good.

Throughout the passage, Webster entextualizes the under-lip as a sign of a terrible laborer – one who is a drone, dull, worse than seven devils as children or a person with Lavater’s straight nose as an elected official. In doing this, he essentializes those with under-lips as biologically different than all other laborers; their lips are “an index of the mind”, “the sign of the commodities for market within”; their lips reveal all of their inner-qualities and capabilities. This essentialism of the human body parallels racism in the way it uses pseudo-science of physical characteristics (lips and skin color, respectively) to measure a person’s inner qualities, and to emphasize a division between capable and incapable laborers. However, it is important to note that, unlike racism, in which skin color and phenotypical features are used as a measure of a person’s inner worth to justify large scale oppression and violence, Webster seems only to use the under-lip to index a person’s labor ability, encouraging discrimination in the hiring process, but nothing more.

Class Distinction

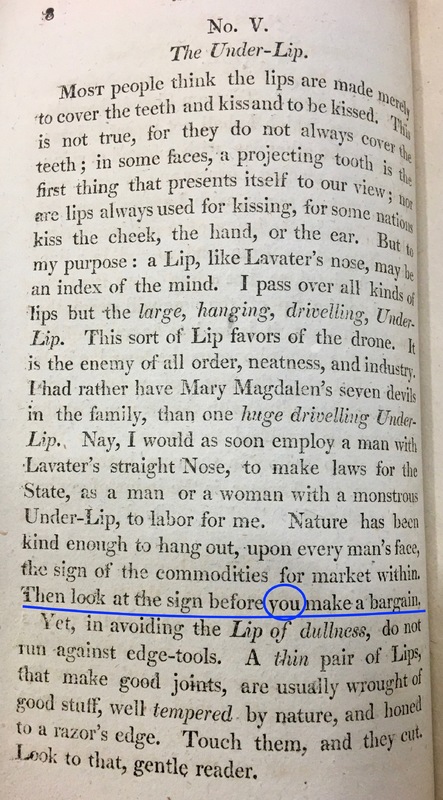

Webster doesn’t just write this passage to insult people with under-lips, though, he writes it specifically to warn his readers against hiring those laborers. In doing so, he entextualizes the difference between the type of man who reads his book (the type who would never have an under-lip), and laborers, who may or may not be cursed with under-lips. The sheer number of insults directed at those with under-lips is enough to suggest that Webster assumes his readers do not have under-lips. He goes on, however, to make the difference between readers and laborers explicit when he writes, “Then look at the sign before you make a bargain” (1808: 8). When Webster directly addresses his readers as “you”, he explicitly shows the difference readers and laborers. While the whole passage talks about lips of laborers, insulting those cursed with an under-lip, it Webster’s purpose is to better inform his readers, those who would never have under-lips, but are hiring laborers who might have under-lips. Webster not only entextualizes two types of laborers – those with and without under-lips – he also re-inscribes the difference between high-class men who read his books and the laborers they hire.